- Home

- Chris Thorndycroft

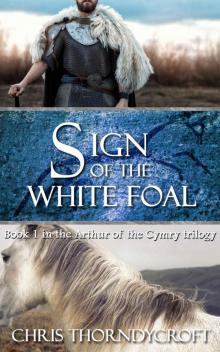

Sign of the White Foal

Sign of the White Foal Read online

Sign of the White Foal

By Chris Thorndycroft

2019 by Copyright © Chris Thorndycroft

All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

https://christhorndycroft.wordpress.com/

For Maia for her constant encouragement and my parents for their unwavering support

Contents

Map of Venedotia 480 a.d.

Family Tree

Glossary

Part I

Part II

Part III

Part IV

A Message from the Author

Historical Note

Sneak Peek – Banner of the Red Dragon

Map of Venedotia 480 a.d.

Family Tree

Glossary

Albion – The island of Britain

Teulu – Warband

Penteulu – Commander of a king’s teulu

Saeson – Saxons (singular – Sais)

Saesneg – The Saxon language (Old English)

Commote – A division of land within a kingdom.

Cair – Fortress

Din – Fort

Afon – River

Lin- Lake

Coed - Forest

“Then Arthur along with the kings of Britain fought against them in those days, but Arthur himself was the leader of battles.”- The History of the Britons

Part I

“My poetry,

from the cauldron

it was uttered.

From the breath of nine maidens

it was kindled.” - The Spoils of Annwn, The Book of Taliesin (trans. Sarah Higley, 2007)

Venedotia (Gwynedd), 480 A.D.

Cadwallon

Night cloaked the coast, turning sand to silver and the hills to slumbering shadows. The moon was shrouded by shifting clouds and beyond the lapping waves the sea was an impenetrable black void. Cadwallon mab Enniaun sniffed the air. The tide was going out, there was no mistaking that stink. But there was something else there too. Perhaps it was his imagination but there was something on the wind that was not right.

“An ill night, lord,” said the young warrior beside him as if reading his thoughts.

“Aye,” Cadwallon replied.

The small camp had overlooked the Afon Conui, nestled on the wooded slope that ran down to the marsh at the water’s edge. The fire had been stamped out and not long ago either. Smoke still curled up from the ashes and the stones that surrounded it were warm. The corpses of the three sentries were warm too, but only barely.

“Poor Gusc,” said the warrior looking down at his slain comrades. “He owed me money.”

“There wasn’t much of a fight,” said the second warrior, an older man whose name Cadwallon seemed to remember was Tathal. “Looks like they were come upon by surprise. Gusc here only had his sword halfway out of his scabbard before some bastard’s knife cut his throat for him.”

“Should we expect an attack?” said the young warrior, a touch of fear creeping into his voice.

“I don’t know.” Cadwallon looked at the long reeds of the marsh below them. That dense foliage could easily conceal a band of warriors. So could the trees of the wooded slope upon which they stood for that matter. Enemies could be everywhere.

“Lord, return to the fortress,” said Tathal. “We can deal with this. It’s not safe for you to be here without an armed escort.”

Cadwallon ignored him. He was right of course. His presence wasn’t strictly necessary and it was probably a little reckless for him to be there but in truth he had welcomed a break from the side of his father’s deathbed. News of three dead sentries and no sign of their attackers had drawn him from his father’s chamber with eager haste.

It was the smell that got to him the most; the smell of death. Not the fast death of slaughter on the battlefield (and at thirty-five summers, Cadwallon had smelt enough of that), but the slow death of old age and sickness. The burning incense did little to mask the stink of sweat and shit, only contributing its own heavy fug to the mix. He had longed for the cool night air and salty tang of the sea. Now he wasn’t so sure.

At their back, straddling twin hills connected by timber palisades, was Cair Dugannu, his father’s fortress; the mighty royal seat of Venedotia. On fine days those twin hills afforded a wide view of seaweed-strewn mudflats, wavering marsh reeds and the deep blue of the ocean, its glassy surface broken only by the curve of the fishing weirs. Further along the coast, the earthworks of the old Roman fort could be seen shielding the port of Penlassoc; a snug little haven where vessels were beached on the mud to trade wine for fish and the fine pearls of the blue mussels that clustered at the mouth of the Afon Conui.

Such were the fine images of youth forever imprinted on Cadwallon’s memory. But tonight it felt as if the darkness was pressing in on all sides, cutting him off from memories of sunshine and cawing gulls, obscuring his sight and threatening to overwhelm him.

He tried to shrug off his foolishness. He was no bard to wax poetic about doom and fate. The kingdom was on the verge of change, that was all. It was natural to feel some apprehension.

And yet... Here lie three dead sentries.

“What’s your name, lad?” Cadwallon asked the young soldier.

“Gobrui, lord,” he replied. “Son of Echel.”

“How long have you been in my father’s guard?”

“Six months, lord. My da was killed in that border dispute with Powys when I was nine. He always wanted me to be a warrior like him so I joined as soon as I was sixteen but…” his voice trailed off. Cadwallon smiled. He knew that the lad had been about to voice his shame that he had not yet made it beyond a night sentry but had thought better of complaining to his lord.

“I’m sure you will become a warrior to match your father’s good name and make his shade very proud one day,” he reassured him. “But take it from me, be careful wishing for war and glory. War is seldom glorious. Take these poor men here. They were come upon by surprise and left this world before they knew what was happening.”

“Are we truly at war, then?” the lad asked.

“Difficult to say until we know who did this,” said Tathal.

“Could’ve been robbers,” offered Gobrui.

“Robbing sentries?” Tathal replied. “Our lads had precious little to steal apart from blades and leather and those were not taken.” He looked at Cadwallon. “You don’t reckon it was… them do you?” He jerked his head in a north-westerly direction.

“They haven’t attacked in a decade,” said Cadwallon. “Why would they now?”

Yes, why now? He thought. Why tonight, of all nights?

He gazed beyond the headland at the narrow straits that separated the mainland from the isle of Ynys Mon. That slim stretch of tidal water was all that stood between them and their age-old enemy. It had been ten years since they had returned. Gaels, Scotti in the Latin tongue; wolves from across the sea seeking land and plunder. Ynys Mon was theirs, ceded to them after years of bitter conflict. The Britons held one side of the straits while the Gaels held the other. He shivered and lied to himself that it was just the chill night breeze from the river. To stare at death every day and trust their lives to the whim of the tides! Manawydan protect them!

“Remain with the bodies,” he said, his voice suddenly more assertive. “I will send down a patrol to bring them back to the fortress.”

“Will you send out troops to scour the woods and marshes?” Tathal asked.

“No. I want all our men within the palisades tonight. I won’t risk ambush by sending out small patr

ols.”

“My lord, there could be a warband lurking nearby. Shouldn’t we at least…”

“No!” he didn’t know why his voice had snapped like that. Was it fear? As Gobrui had said, tonight was an ill night…

He left them then and headed up the slope towards the fortress.

Cair Dugannu had been fortified by his father after his grandfather’s original holdfast on Ynys Mon had fallen to the Gaels. The return of the hounds of Erin had been a sore blow to the dynasty that had driven them into the sea a generation previously. After Rome had abandoned Albion, Venedotia, like the rest of the province, fell vulnerable to those who had never borne the yoke of the iron legions. Gaels plundered and settled in the west just as the Saeson did in the east and the Picts in the north. Facing barbarians on all sides, the Council of Britannia, an assembly which was hastily formed to administer their newfound independence, struggled to keep the old province together. Out of desperation, the Council’s leader, Lord Vertigernus, had decided to fight fire with fire.

In the north dwelt a client tribe who had served as a buffer zone between Rome’s northernmost border and the howling, blue-painted Picts that lived in the hills beyond it. Cunedag was their leader and a more ferocious warlord Albion had rarely seen. His standard was the red dragon, the origins of which lay in the carven standing stones of the Picts, for that people’s blood flowed strongly in his line.

Cunedag was descended from Padarn Redcloak; a Pictish chieftain who had accepted a military rank from Rome and swapped barbarism for toga and trade. As Lord Vertigernus aped his Roman predecessors, so had Cunedag followed in his ancestor’s footsteps. He and his sons took up the offer of butchery for pay and marched south to Venedotia.

Nine sons of Cunedag there were; Tybiaun, Etern, Ruman, Afloeg, Caradog, Osmael, Enniaun, Docmael and Dunaud. Together they brought fire and sword to the Gaels and forced them back in battle after bloody battle until only the island of Ynys Mon held out against them. That battle was the bloodiest. Tybiaun and Osmael fell but the Gaels were finally sent back across the sea whence they came.

The dragon standard was planted deep into the soil of Ynys Mon and the sons of Cunedag came to be known as the ‘Dragons of the Isle’ with Cunedag as their chief; the Pendraig. Before he died, he divided his kingdom between his surviving sons. To Etern went Eternion, to Ruman Rumaniog, to Afloeg Afloegion, Caradog Caradogion and Dunaud Dunauding. Meriaun – the son of Cunedag’s fallen firstborn who had excelled himself by slaying the Gaelic chieftain Beli mac Benlli – was also given a portion; Meriauned.

The only son who did not receive a kingdom was Cunedag’s seventh and favourite son Enniaun, known as ‘Yrth’, the impetuous. Cunedag had groomed Enniaun to rule as Pendraig after his passing. But when old Cunedag finally died and Enniaun succeeded him as High-king of Venedotia, the other rulers began to grumble at being subservient to their younger brother.

Envious eyes looked upon the dragon standard but the return of the Gaels had kept the Venedotian kings too busy to do anything about it. The wars were long. Ynys Mon was lost and the Dragons of the Isle grew old. One by one they died and were succeeded by their sons but family rivalries still burned deep. When King Afloeg died without an heir, Enniaun Yrth absorbed his kingdom on the Laigin Peninsula into his own lands, an act which caused further grumbling.

Although a fragile peace between Briton and Gael had reigned for many years now, the wars had turned Enniaun Yrth into a battle-hardened old warrior every bit as ferocious as Cunedag had been. None of the other kings dared act on their resentment while he still lived. Instead, they bided their time, knowing that one day a new king must be crowned Pendraig.

Cadwallon strode in through the west gate and made his way up the north hill where the Great Hall stood. He gave orders to a sergeant to dispatch a patrol to retrieve the slain sentries. A servant was relighting the torches that were sputtering low. All were still awake and about their duties. Few would sleep that night, least of all him.

The night was dark. The enemies innumerable. And in a chamber on the upper floor of the royal quarters, the Pendraig was dying.

The attack came before dawn. Enniaun had died in the small hours. Cadwallon was in the Great Hall, a horn of mead in his hand. He wasn’t grieving. The old warhorse had been over sixty and had been a difficult man to like at the best of times. No, his thoughts dwelt on the immediate future.

To all intents and purposes, he was now the Pendraig, High-king of Venedotia. There would be a coronation ceremony of course and all the other kings – his cousins and remaining uncle – would come to pay him homage. Some had already visited his father’s deathbed when it became known that his time was near. Some had been conspicuously absent and their names had been noted.

His wife Meddyf entered the hall and joined him at the table.

“How are the boys?” he asked her.

“Sleeping, at last,” she replied. “They were tired but they did their duty and paid their last respects to your father.”

“How are they?”

She shrugged. “Maelcon acted like he didn’t care which may be the truth for all I know. Guidno was upset but I think he was just scared. They weren’t close to your father, after all.”

“No,” Cadwallon agreed. “Few were.”

She poured him some more mead from the jug and took the horn from him, drawing a long sip herself before setting it down. “Will you be coming to bed soon?”

“No. I can’t sleep.”

“Thinking about the future?”

“I’ve been thinking about the future for many years now for all the good it did.”

“Surely after so long you feel ready to be a king?”

He looked at her. “Do you feel ready to be a queen?”

She was silent for a while and then placed a hand on his arm. “We have known this day was coming for a long time,” she said. “All is as it should be and that must be enough for us. Let us rest our heads in the lap of fate and be content.”

He didn’t answer her. As always, she sensed his mood and was trying to quell his concerns, good wife that she was. He couldn’t hope for a better one and he needed her now. He wanted to tell her about the dead sentries. He wanted to tell her his deepest fears, not just about that night but about all the nights and days to come. But what sort of a husband would that make him, to burden her with his own troubles? What sort of a king?

The door to the Great Hall crashed open and Tathal staggered in. “My lord!” he wheezed, evidently having run up the north hill. “We are under attack!”

Cadwallon felt the warmth the mead had brought him suddenly drain from his face and a chill came over his heart. He slammed the horn down and stood up. “Bar the gates!” he said. “Man the palisades! Wake every warrior! Why do I not hear the warning bell?”

“The guards on the western palisade have been slain, lord. Nobody can get to the bell. They came upon us under cover of darkness and scaled the palisade with ropes and grappling hooks.”

“Who, in the name of the gods?”

“The Gaels.”

Cadwallon felt his stomach sink. What a fool he had been! They must have crossed the straits at the Lafan Sands at low tide earlier that day and waited in the marshes and woods. They had even slain his sentries and still he had not sent out patrols!

“They have us pinned on the north hill,” Tathal went on. “The southern hill and the lower fortress fell but not before I sent a messenger out the east gate. With any luck he will make it through to Din Arth and get word to your brother.”

Cadwallon turned to Meddyf. “Go and stay with the boys,” he told her. “Bar the door.”

“Where are you going?”

“I am the lord of this fortress now,” he replied. “My place is on the palisades.”

Tathal followed him out of the hall and they crossed the enclosure to the palisade that ringed the north hill. The gate was barred and every remaining warrior had marshalled on the rampart that faced south, overlooking

the small valley between Dugannu’s two hills. In that dip lay a cluster of roundhouses, pig runs and workshops. As Cadwallon climbed up to the rampart, he could see the Gaels ransacking and burning the homes of his people. On the other side of the dip the southern hill with its barracks and granary was already under Gaelic control.

“I’ve failed them…” he muttered. “May the gods forgive me, I’ve failed them!”

They could hear the screams of the fortress’s inhabitants as glowing sparks whirled up into the night sky. The sun has not yet risen on my reign and already I am defeated! How had they known? How had they known?

The Gaels marshalled on the footpath that led up the side of the north hill. Cadwallon’s men had a few bows between them and several arrows were sent down into the mob who quickly raised their shields and advanced on the gate.

The defence did not last long. A battering ram was brought forth and heaved against the gate by ten men, shields covering their heads. Cadwallon, Tathal and the remaining men on the palisades descended to ground level and formed a defensive line in front of the gradually splintering gate.

“You should go and be with your family, lord,” said Tathal.

“No,” Cadwallon replied. “I brought this upon us. My fate will be no different to yours. I should at least be able to die in battle.”

The gate came down and the Gaels spilled in, falling upon the spears of the Britons with blood-curdling war cries. The line held for a moment but eventually, inevitably, the Britons were overwhelmed. The line broke and the fighting descended into the chaos of one-on-one combat.

Cadwallon roared as the pent-up shame and fear finally found an outlet and he reddened his sword in Gaelic blood. Tathal, loyal warrior that he was, kept himself ahead of his new king, hacking and slashing like a man twenty years younger.

Sign of the White Foal

Sign of the White Foal